I’ve prepared filet steaks several times over the last 50 or more years (although only this once since starting this blog ten years ago), but this was the first meal in which I had water buffalo to work with.

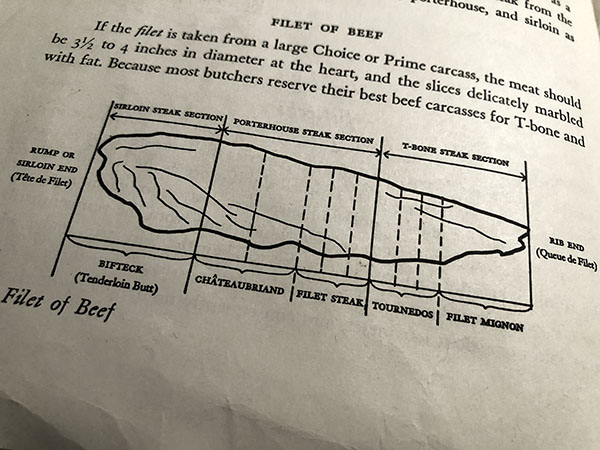

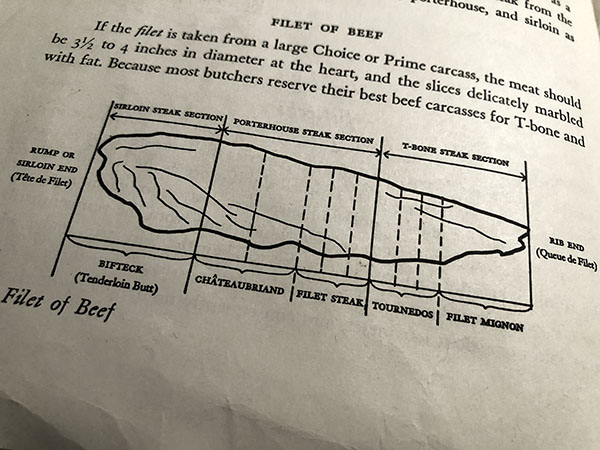

First, what’s a filet steak?

Because of the difference in the animals’ sizes, it might be hard, using only their appearance and weight, to translate water buffalo cuts into the names used with taurine cattle, which is the umbrella category for most modern cattle breeds (I hope I have this right), but I’m going to call what we enjoyed last night, ‘filet steaks’, even if I prepared them like tournedoes, which are still smaller than filet cuts.

In any event, they were delicious. The steaks were quite small, as they should be, coming from the end of the whole beef filet (and buffalo are smaller than American cattle), but since they were so intense in flavor and texture, a scant 4 ounces felt like enough, especially since we enjoyed the juicy pork wrapping as well.

Only incidentally, they tasted more like good venison steaks than any beef we’d ever had, which is no bad thing.

Finding the filet steaks was easy, and almost pure serendipity; preparing them took weeks (I found that it’s not easy to find a source of fresh pork fat in the 21st century, even checking with real butchers), but last night I was able to assemble the tournedos within a few minutes, then I set them aside for an hour or more, to concentrate on what I was going to do with the vegetables.

- two frozen water buffalo filet steaks (4 ounces each) from Riverine Ranch in the Union Square Greenmarket, defrosted, wrapped with strips of fresh pork belly obtained from Joseph Ottomanelli, one of the brothers who run their family’s iconic shop on Bleecker Street (I separated the outer, skin layer from the one inch-wide sections on the kitchen counter, and secured them with both toothpicks and butcher’s string), dried with paper towels, pressed with one and a half teaspoons of crushed black peppercorns, sandwiched in wax paper and allowed to rest for over an hour before they were sautéed in a mixture of butter and olive oil inside an oval enameled cast iron pan for about 3-4 minutes each side, removed, seasoned at this point with sea salt and kept warm, the butter, oil and accumulated meat fats removed from the pan, 2 teaspoons of sliced ‘yellow shallots’ from Norwich Meadows Farm added along with a little butter and stirred for just a minute, 2 or 3 tablespoons of good beef stock poured in and boiled down until thickened, while scraping up the coagulated cooking juices, followed by 2 tablespoons of Courvoisier V.S. cognac, which was boiled until its alcohol evaporated [that process quickened this time by an unexpected explosion of fire in the pan as I poured the brandy in, which I was able to quickly blow out], and then, off heat, one or two tablespoons of butter swirled into the sauce about half a tablespoon at a time, while stirring, the sauce then poured over the filets

- close to a pound of some beautiful small parsnips from Windfall Farms, scrubbed, trimmed, and kept whole, tossed with olive oil, salt, freshly ground black pepper, a little crushed dried habanada pepper, and branches of rosemary from Phillips Farms, spread in a single layer onto an unglazed ceramic oven pan, roasted at 400º

- wild cress from Lani’s Farm, drizzled with a small amount of a very good olive oil, Badia a Coltibuono, Monti del Chianti, from Chelsea Whole Foods Market

- six Maine cherry ‘cocktail’ tomatoes from Whole Foods, slow-roasted whole inside a small antique tin oven pan after they had been rolled around inside in olive oil, a generous amount of dried oregano from Norwich Meadows Farm, and one large garlic clove from John D. Madura Farms, sliced into 6 sections

- the wine was a French (Loire/Chinon) red, Chateau du Petit Thouars, Chinon Rouge ‘Les Georges’ 2016, from Flatiron Wines

- the music was Hindemith’s 1934-1935 opera, ‘Mathis Der Maler’, Simone Young conducting the Hamburg State Philharmonic Orchestra and the Hamburg State Opera Chorus (“The story, set during the German Peasants’ War (1524-25), concerns [the historical protagonist, the painter Matthias Grünewald‘s] struggle for artistic freedom of expression in the repressive climate of his day, which mirrored Hindemith’s own struggle as the Nazis attained power and repressed dissent. The opera’s obvious political message did not escape the government’s notice.” citation from Wikipedia)

[the image of a diagram of a whole fillet of beef is from my much-worn copy of Julia Child’s beautiful book, ‘Mastering the Art of French Cooking’]